A DuPont framework to measure VC performance

1. INTRODUCTION

Venture Capital ("VC") as an asset class has captured the public imagination of late. But unlike in public market funds, where benchmarks and factor models allow for a dissection of performance to truly separate the legendary investors from the rest, there seem to be few frameworks to evaluate VC funds. Newbie investors to this asset class often fall prey to the trap of focusing on just one or two historical metrics (e.g., IRR) that are easier to calculate – but don't necessarily capture the real drivers of returns that are replicable over cycles.

Even seasoned institutional investors (and I have spoken to at least a hundred over the last year) often focus on one or two touchy-feely catchphrases ("what's your edge in attracting great entrepreneurs", "what are your thesis areas"), without being able to articulate what truly separates a the best VCs from the rest.

2. NET REALIZED IRR: THE HOLY GRAIL

The legendary Sir John Templeton was widely regarded as one of the world’s wisest investors. His first maxim was to invest for the long term.

“The true objective for any long-term investor is maximum total real return after taxes.” - Sir John Templeton

But Sir Templeton's maxim was generally about stocks, which are liquid securities that can be bought and sold on an exchange [1], not about privately held instruments which, like small-cap stocks, "trade by appointment".

An investor in the private market, therefore, needs to sharpen the focus from maximizing total return to achieving maximum total realized returns. In other words, the objective of investors in a Venture Capital Fund is to maximize Net Realized IRR.

The DuPont framework for breaking down ROE was the original inspiration for writing this article. I'll admit, while I love algebra (though the simpler, the better), I don't have an actual equation to break down Net Realized IRR into its mathematical components. Instead, I focus on breaking down the drivers of each of these three terms so that investors can truly determine whether a fund or its management team exhibits the factors or drivers that will determine outperformance over multiple investment cycles.

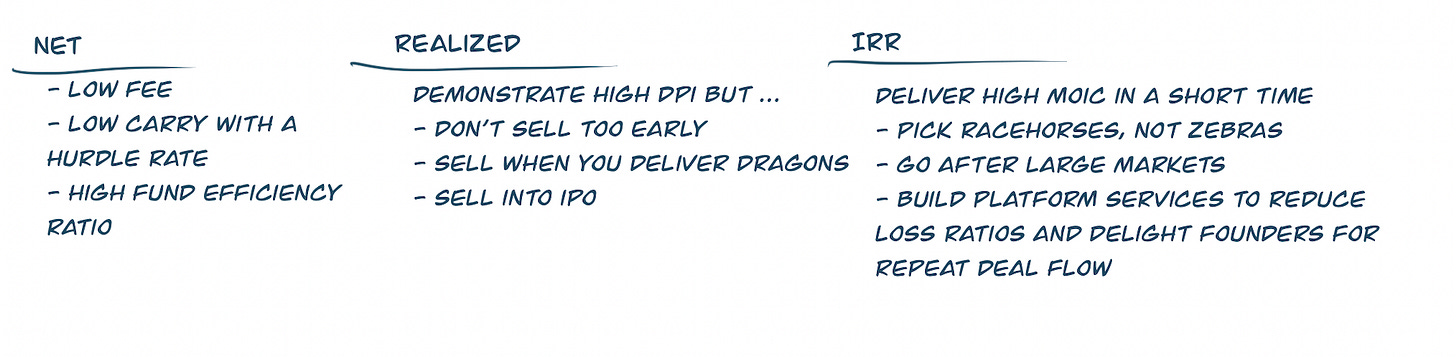

3. NET

Investors pay fees and costs to their fund managers that reduce their return on investment. The principle of focusing on rock-bottom costs to get higher returns has long been espoused by John Bogle, founder of Vanguard.

"Gross returns in the financial markets minus the costs of financial intermediation equal the net returns actually delivered to investors." - John Bogle

Simply put, Net is what is left for an investor after all costs (base fees, administrative costs, and performance fees) have been deducted. Low fees, low costs and low performance fees mean higher net returns for the investors.

The guiding principles to determine the ideal fee or carry structure are:

Fee

Most early-stage VC funds are structured as 10-year vehicles. A competitive fee structure is one that tapers after year 4 or 5 from 2% down to around 1.0-0.5% for the rest of the term.

I am sympathetic to a larger fee structure for smaller VC or Private Equity ("PE") funds, simply because carry-tolls are levied only on exits and not on an annual basis as in public market funds. As a result, the Partners and team in a small-sized VC fund often need to work for a decade before they can see remuneration that would be comparable to market salaries for their skills and work in other industries.

"Performance fee", "Carried Interest" or "Carry"

The history of carried interest has its roots in the Venetian Middle Ages, where sailors and merchants took on the actual risk of a long-distance voyage by raising money from investors for a 20% share in the profits of the expedition [2]. Investment funds often share profits in the same way. This is capitalism at its finest, where the best talent will charge a share in the upside (called "performance fee", "carried interest" or "carry") for making your money work for you.

As an investor, you should consider imposing a hurdle rate or a minimum acceptable rate of return over which a manager is compensated with carry. A carry structure without a hurdle rate rewards managers that may not even beat inflation.

Ideally, investors should look for a fund where carry kicks in only after an inflation hurdle rate (with a "catch up" so that the hurdle rate compounds even in down years, where the manager's performance has been sub-par).

The standard carry charged by VC and PE funds is 20%, but marquee funds may charge as much as 30%. This heavy carry structure has all but disappeared in public markets, where carry is generally in the 10% to 15% range.

As a general rule, the best and the most consistent managers will charge a larger carry. While you should be easily able to verify this performance, an investor should also beable to predict the reasons the performance will sustain.

Fund efficiency ratio

The efficiency ratio of a fund is the amount of dollars available for investing (“Invested Capital”) divided by the amount given to the fund by investors (or “Paid-in Capital”)

Invested Capital is the amount available after fees are deducted to run the fund. A low fee structure means higher Invested Capital.

You can only make returns on Invested Capital. The end goal is to achieve returns on Paid-in Capital given to a fund by investors. It follows that managers that start with a lower investible amount need to earn much higher returns than managers that start with a higher investible amount.

But a oft-forgotten lever to increase Invested Capital is to be able to reinvest any early realized gains back into companies rather than returning this to investors.

The two levers of fee and reinvestment can be used to increase the efficiency ratio, which should ideally be more than 90% for the best VC funds.

4. REALIZED

Realized returns refers to the returns that are actually made by the fund upon selling its investments for cash. This includes capital gains, dividends and interest (if any).

Unfortunately, there is no way to forecast realized returns. The best funds take advantage of bull markets and valuation increases to generate a bit of liquidity from their portfolio at regular intervals.

In the VC power law business[3], though, this sometimes involves violating Peter Lynch’s principle

“Selling your winners and holding your losers is like cutting the flowers and watering the weeds.” - Peter Lynch

So how does one figure out what the right time is to sell? There are no easy answers here, but some guiding principles may help identify managers who have developed a “selling muscle”

Don’t sell too early in the fund life. A business takes a long time to grow and mature. If a fund's initial ownership in a business in the Seed round is in the high teen %, the rule of thumb is you will have around half of your initial ownership by the time the business hits unicorn status. Selling out too early means a fund manager is trading off early IRR for much larger dollar gains in the future.

Start selling when you deliver "Dragon" outcomes. A Dragon is a company that returns the entire fund – a fund maker [4]. At this point, the value of a fund's shareholding in a single company is more than the size of the total fund. At this stage, the fund's ownership now has been de-risked and instead, the risk has perhaps tilted towards depressing future returns ("even tall trees don't grow to the sky"). This is borne out in real life too – because the typical new, incoming investor into the company at this point is a private equity (or like fund) that inherently focuses more on safety of principal in exchange for predictability of growth and earnings and lower IRRs than delivered to early-stage investors.

A popular LP question is to ask why don’t VC funds sell into "secondary" sales [5]. In my opinion, this is a trite question that ignores the reality of secondary markets. Secondary sales in private markets take place only under some conditions:

When a round is oversubscribed and there is more demand for shareholding than a founder is willing to give up. In this case, the company absorbs the primary capital and the incoming investor buys some shares from earlier investors to reach their target shareholding. This is the best form of secondary from a seller’s perspective, as the discount [5] to the primary round price is the lowest.

When a new investor actually wants to invest at a lower price. Often, the entrepreneur is able to convince a new investor to invest primary capital at a higher price and buy off some secondary shares from early investors at a steep discount. This is a simple mix of acquiring the same shares at two different prices to facilitate the perfect blended price for the incoming buyer

When there is at least a one round pause between an investment round and a sale. Selling right after you have recently invested involves the "signalling risk" of new investors perceiving that you have lost confidence in the company, its business or its founders.

Finally, the simplest way that investors can look at realized returns is to look at the cash paid back on previous funds. Distributions to Paid-In ("DPI") is a well-tracked metric, but it penalizes new managers – funds with a longer history across cycles will obviously be able to demonstrate this while new, unseasoned funds can only promise this.

Selling into an IPO: This obviously generates liquidity for investors, but the number of funds doing this has come down dramatically. As a leading US college endowment manager pointed out to me, the breakdown between realized and unrealized returns has changed over time. Anecdotally, during the dot-com boom of the 1990s, VCs were delivering higher realized gains as they were legally unable to hold shares post-IPO and had to distribute their shares to investors upon listing. In contrast, most VC funds are now able to and often hold on to public shares for much longer (and continue charging fees on the same). As a result, the difference between total gains and realized gains in the dot-com era was much smaller than in 2021.

5. IRR - and the factors driving it

Thr returns generated by investing activities itself is, by far, the most important piece. After all, lower fees, costs and carry have no impact if the underlying investments themselves don’t deliver high returns in exchange for the illiquidity and long duration of the investment.

But a breakdown of the IRR equation into its two components is revealing. The best IRR is delivered by returning high Multiples on Invested Capital ("MOIC") in the lowest possible time.

But how does a manager deliver high returns quickly?

This is where most of the touchy-feely stuff in VC decks comes in. Most VC decks will have slides around "we have a great network", "great investing team", but the real reasons to do all the things that VCs do below is to find the best entrepreneurs.

Venture Capital's real job is to find Racehorses, not Zebras.

Horses and zebras and ponies are all part of the genus Equus. They share the same characteristics: odd-toed ungulates with slender legs, long heads, relatively long necks, manes, and long tails – but no one expects a zebra or pony to outrun a Throughbred racehorse over any distance.

A VC's main job then is to find the best entrepreneurs – Thoroughbreds – and to avoid picking ponies and zebras, or hope that they will someday be racehorses.

The best funds tell us over and over again how they find, and sometimes even beg the best founders to take their money [6]. Less successful funds who are not able to find the best founder-entrepreneurs end up spending an inordinate amount of time coaching, guiding and counseling them to help their businesses become better. Like any French chef will tell you, the quality of the ingredients determine the quality of the sausage — a cook can only do so much.

Go after large markets

One of Warren Buffett’s better-known aphorisms is about how a good entrepreneur cannot make money in a bad market.

"When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact." - Warren Buffett

In my view, the popular term “Product/Market Fit” (attributed to Andy Rachleff of Wealthfront and Benchmark Capital) has it completely backwards. Far too many founders take Product-Market Fit as an exercise in endlessly tweaking their product to find the right market, or until they run out of money. A bad market is a bad market, period.

If you instead invert the term into “Market/Product Fit” so entrepreneurs focusing on a large market that is up for grabs, and then build products that can grab a large share of the volume and consequently profits in that market. This lesson was internalized by the legendary Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital, who said that his primary rule was to “target large markets”

"We’re never interested in creating markets – it’s too expensive. We’re interested in exploiting markets early.” - Don Valentine

Platform

Platform teams at VC funds offer resources to entrepreneurs in addition to money and partner time and expertise. These involve a lot of effort on the part of the fund manager, and primarily exist for just two reasons: to reduce loss ratios [7] and to delight founders that return to them or refer to them.

Reduce Loss Ratios

“The VC business is a high-risk one — we fund companies at their earliest inception (often when they are merely founders with an idea of what they intend to build but no demonstrable product or service), with the idea that most of these companies will not yield significant economic value.” - Scott Kupor, a16z

One way to increase the probability of success of these companies (and reduce the VC’s loss ratio) is to provide platform services such as talent acquisition or recruiting, Go-to-Market support to help in customer acquisition or discovery (particularly for enterprise companies), Capital Networking to connect portfolio companies to the best possible pools and providers of capital around the world and other services or learning opportunities such as marketing, branding or even a community to exchange business and operational skills.

Delight founders for repeat deal flow

Having the best deal flow is the single largest critical performance driver in the VC industry. Marc Andreessen of Andreseen Horowitz (a16z) puts it clearly:

“To succeed in venture capital you must be one of the top five firms. And to get there, you must have amazing deal flow.” - Marc Andreseen

Andreseen Horowitz knows exactly why they spend so much energy on platform services :

“The popular view of venture investing is that it is about picking good companies, because that’s what’s important with public equities. But you can’t apply the logic of public equity markets, where by definition anyone can invest in any stock. Success in VC is probably 10% about picking, and 90% about sourcing the right deals and having entrepreneurs choose your firm as a partner." - Chris Dixon, a16z

A platform offering that delights entrepreneurs is the surest way to ensure that the best entrepreneurs will choose to work with your VC firm.

Measuring Historical performance

Early stage venture is largely a business of repeatedly attracting and picking the best entrepreneurs. Most sins are those of omission, not of commission as the amounts at-risk in early stage investing are small.

In a world of power-law returns, the costs of missing out were higher by far than the risk of losing one times your money. - Sebastian Mallaby, The Power Law (p. 252). Penguin Books Ltd

Most diligence around past performance of funds involves slicing and dicing the data to compute:

Fund performance by vintage (how a fund's performance compares to others during the same period)

Investment performance by sector (does the manager have an investing edge in one sector over another?)

Investment performance by investing partner (are all the partners equally talented? If not, are more dollars being allocated to the more talented partners or teams?)

Investment performance by original partner vs current partner (if the current partner managing the investment is different from the original investing partner; are these individuals better at 'sowing' or 'growing')

Investment performance by stage (is the manager more talented at picking initial investments, or at doubling down on the winners from their portfolio)

These are only a few ways of measuring historical performance, and the idea here is to be able to determine whether past performance is repeatable.

6. SUMMARY

While not strictly an equation, this DuPont framework to measure VC performance is useful in providing a method to dissecting each word in the phrase Net Realized Returns and identify factors that contribute to sustained outperformance of venture capital funds.

I hope you find this useful in making a decision when managers approach you to invest in a Venture Capital fund.

For the purpose of this exercise, I have ignored the terms real and after taxes – within an asset class, investors have limited control over macro factors such as inflation; while taxes require the attention of CPAs, CAs and other such specialists to help minimize them.

1. Liquidity means the (in)ability to trade a security in exchange for cash or equivalents

2. Fee.org, https://fee.org/articles/the-medieval-geniuses-who-invented-carried-interest-and-the-modern-barbarians-who-want-to-tax-it/

3. Peter Thiel was the first venture capitalist to speak explicitly about the power law, where a handful of winners would dominate the performance of the whole fund. Sebastian Mallaby, The Power Law (p. 209). Penguin Books Ltd

4. Unicorns vs Dragons, Techcrunch, https://techcrunch.com/2014/12/14/unicorns-vs-dragons/

5. A secondary sale is a sale of your shares to another investor. In contrast, a primary investment is an investment for fresh shares where the money directly flows into the company. Secondary sales in privately held companies usually takes place at a discount to the primary price in exchange for the buyer providing liquidity to the seller.

6. See Chapter 11: Accel, Facebook, and the Decline of Kleiner Perkins - Sebastian Mallby, The Power Law (p. 249). Penguin Books Ltd.

7. Loss ratio is the number of investments that ended up being worth zero, and alternately, the capital invested that went to zero out of the total capital invested. See https://avc.com/2013/11/loss-ratios-in-early-stage-vc/